Event Write-Up: Reconstructing Evensong according to the 1560 Latin Prayer Book (LPP)

This blog post is drawn largely from a talk delivered by Alexander Trowell in Keble Chapel on the 16th May 2023, before the service. Revised September 2024 for presentation here.

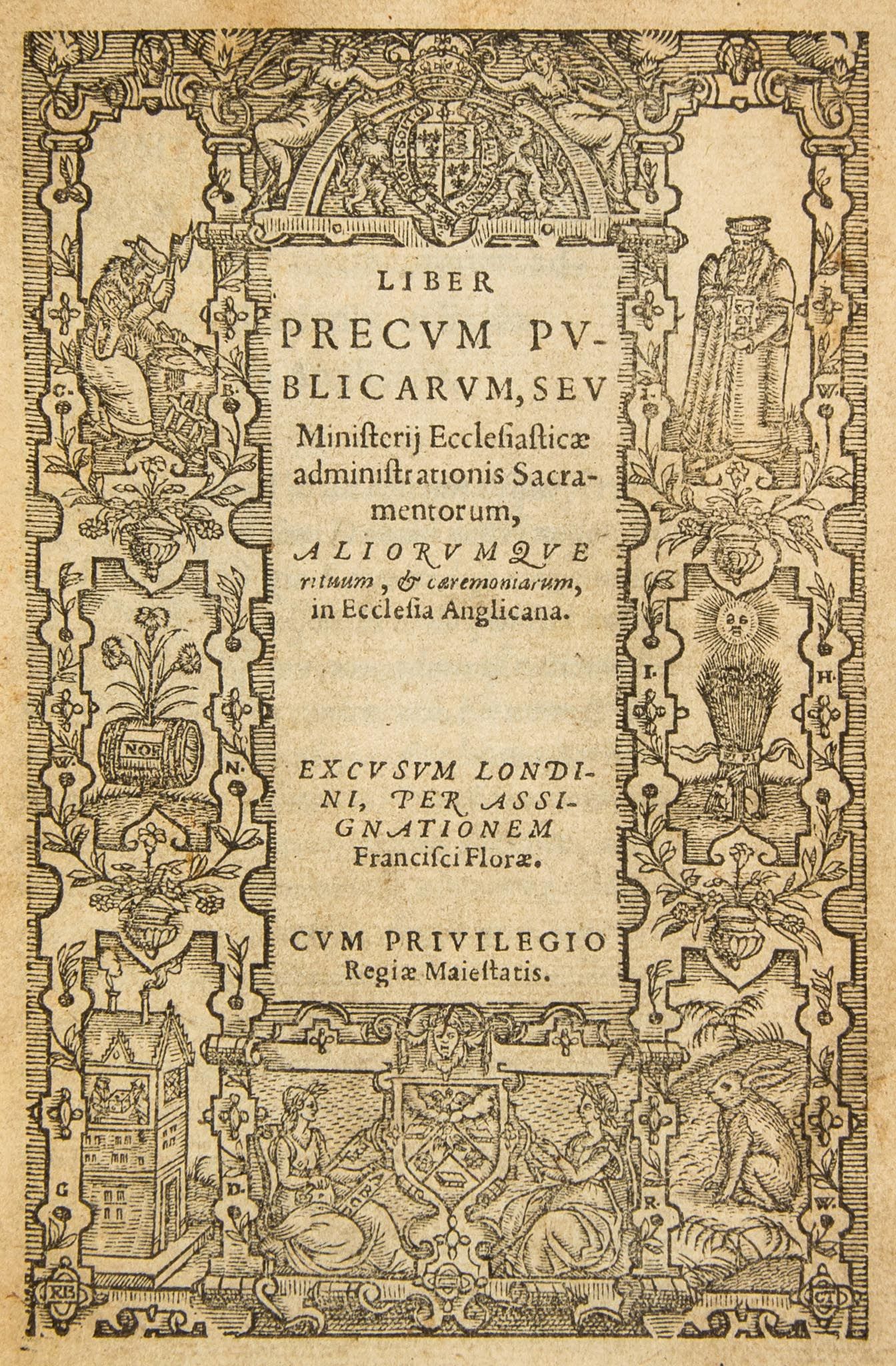

Introduction to the Liber Precum Publicorum

The Liber Precum Publicorum ( hereafter LPP ) is one of the most elusive liturgies of the Church of England. It is the work of a man called Walter Haddon, who was apparently largely unqualified to make such a liturgical book. [1] He was a lawyer and his rather clumsy use of Latin is said to resemble that of legal documents and not The Liturgy. However, he is not only to blame, Haddon’s 1560 LPPdraws heavily on its Edwardine predecessor by Scottish theologian Alexander Alesius. It is likely these translations were made hastily follwing respective English versions to provide places of learning with suitable liturgy.

The 1560 LPP was considered too conservative by some. It is first worth noting a key point. During the English reformation, the Latin language was not usually seen as intrinsically bad or Popish. Reformers wanted people to worship in their vernacular – and this does not necessarily exclude Latin in learned circles. To the modern critic, the natural assumption is that Latin was intrinsically conservative – indeed to have a Latin Book of Common Prayer might seem contradictory or ridiculous. However, Article XXIV reads:

It is a thing plainly repugnant to the Word of God, and the custom of the Primitive Church, to have publick Prayer in the Church, or to minister the Sacraments in a tongue not understanded of the people.

The instruction is not that services can no longer be in Latin. It was entirely appropriate for the chapels of the three public schools and two universities to continue services in Latin albeit in their new Prayer-Book-format. Indeed, article XIV of the Act of Uniformity of 1662 renews the provision for Latin services “in the Chappells or other publique places of the respective Colledges and Halls in both the Universities in the Colledges of Westminster Winchester and Eaton and in the Convocations of the Clergies of either Province”.[2]

Furthermore, all those educated in the pre-Commonwealth school system would have had extremely good Latin. It is often commented that Shakespeare after two years in a Tudor grammar school had “little Latin and less Greek”, but in fact he probably had better Latin than most people who hold an undergraduate degree in Classics from this country’s top universities.[3] Elizabethan clergy were encouraged to use Latin in their private devotions.[4] This can bee seen in the writings of Archbishop Laud.[5] 16th century bishop John Jewel put it:

“The tongue is nothing but tongue. It is the matter and meaning of the words that is mystical.”

The pre-Commonwealth Church of England was never really concerned with the idea that to worship in Latin was in any way “Popish”.

If it was not the Latin that upset people, what did? Although notionally the 1560 LPP was a translation of the 1559 prayer book, it in fact drew material from the early and much more conservative, “catholic”, Edwardine 1549 prayer book (what Alesuis’ Latin Prayer Book was based on). Although this cross-over of material might simply be put down to a failure on Haddon’s part to exclude or edit out those 1549 parts, scholars have generally ruled out that possibility. It is more likely that the conservative, often recusant, Oxford clerics preferred this more “catholic” style. The main objections were regarding the following: the 1560 LPP allowed for reservation of the sacrament; a fuller Kalendar and; an epistler and gospeller vested in copes at the Communion.[6] Reservation was the big one; it had been practised in from the Medieval English uses, and kept in the 1549 prayer book, but removed from the more reformed 1552 Prayer Book. Somehow then, Haddon managed to slip this and other conservative, High-Church features into the 1560 LPP, presumably deliberately copied from Alesius’ Latin 1549 Prayer Book. Unsurprisingly, this did not go unnoticed.[7] Although this was not such a problem amongst the clerics of the University of Oxford, the rather more Puritanical clergy at the University of Cambridge were disgruntled: most colleges refused to use Haddon’s LPP, services were switched to English despite the fact the rest of the university’s operations would have been conducted in Latin.

Another difference between the 1560 LPP and its companion English 1559 Prayer Book is the confession at the start of the offices. The LPP does not have a confession before the start of Mattins and Evensong. Archbishop Cranmer added this vorspiel to the offices in his 1552 Prayer Book and it remained in the 1559 version too. John Harper suggests that Cranmer adds the confession because the Communion (which contains a confession) was happening much less frequently by 1552, he writes:

“the appendage of the introductory rite to both Offices in 1552 probably reflects the need to include a confession on days when Holy Communion was not celebrated.”[8]

This might reveal something about Low vs High Church practice: even by 1552 communion was happening much less frequently, but in conservative, High Church college chapels, i.e., in Oxford, but not Cambridge, the Communion was still frequently being celebrated so the 1560 LPP did not need this addition.

The 1560 LPP though being a significant historical document is little heard of today. Many subsequent Latin Prayer Books were made by liturgists helpfully and rather more frequently, unhelpfully “correcting” the earlier books’ “mistakes”, always with a High Church, Low Church or scholarly agenda in mind. However, only Alesius’ 1549 Latin Prayer Book and the 1560 LPP received official mandate for their production and use.

The continued production of Latin Prayer Books indicates a continued interest in them and use of them in college chapels.[9] Interestingly Latin services at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford were discontinued as late as early 1862, presumably as ecclesiastical tastes were rapidly changing as the Oxford Movement and the reaction against it swept across the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Emancipation.[10]

Music of the LPP

The fact that the LPP’s use was far from wide-spread, means there is not a great deal of music associated with it, indeed there is no music surviving that scholars can say with total certainty was intended for use with the LPP. There are a few potential sources of music for the LPP services:

- People may try to tell you there was no plainsong after the English reformation – they are wrong! There was, of course, John Merbecke’s The Booke of Common Praier Noted which is an example of how people adapted pre-Reformation chant to the new vernacular words. It would seem canticles and psalms were probably sung to the Sarum tones.[11] This is exactly what Merbecke provides too. Responses were probably a similar case. Later Victorian publications of English plainsong such as Briggs & Frere capture more-or-less what English choirs might have been doing c.1600 too. This can be extended to LPP services.

- Pricksong (or better known by its French name: Chanter-sur-le-livre). This was a widespread technique by which singers would improvise harmonies and melodic lines over an existing plainsong melody. The success with which this was ever achieved is debatable, there are certainly many continental accounts of the results being very unsatisfying. There survive a number of examples of written out harmonised English psalm-chants (these are the beginnings of what become known as “Anglican Psalms”) and similar style works (such as Tallis’ setting of the Litany). [12] It seems very likely that plainsong responses and psalm tones or some other bits of chant as described above would have, on occasion, been embellished with simple harmony written out or improvised: possibly a few fauxbourdons concluding with a cadence to the shape of the plainsong line.

- “Here’s one I made earlier”. Though I have not seen any musicologists or liturgists comment on this, I think we can speculate that since many colleges and schools owned large libraries of pre-Reformation or Marian Latin polyphony, so long as the words did not have any problematic theology, I see no reason why these could not have been sung in LPP Certainly, choirs took this approach even in English, taking older pieces of polyphony supplying new or translated words. For example, O Sacrum Convivium[13] by Thomas Tallis is thought to be based on earlier English motet I call and cry to thee. This was put to the Latin words to be used as the Magnificat antiphon for the feast of Corpus Christi and then later translated into English as O Sacred and Holy Banquet[14]. Exactly this can be seen in the Peterhouse partbooks, former and latter sets, which were copied for use in High-Church Peterhouse Chapel.

There exist examples of polyphony that were likely written specifically for the LPP. One such example is Thomas Weelkes’ Laboravi in Gemitu, one of only two Latin motets (not including macaronic works). The other is O Vos Omnes. In 1602, Thomas Weelkes was awarded a BMus from Oxford having been a member of New College. At that time, those supplicating for such a degree had to submit a composition.[15] It is noted in the register of New College that Weelkes offered a ‘hymnum coralem sex partium’. This could have been either Laboravi or O Vos. Laboravi is an imitation of an earlier motet of the same name by Phillipe Rogier (which was also imitated by Thomas Morley). This therefore may have been a compositional exercise, perhaps university coursework, in effect. Weelkes was previously organist at Winchester School – which also used the LPP; it is possible one motet was for Winchester and one for Oxford, or both for Oxford – we can never know for sure – but they were both likely intended for LPP liturgy.

Another such example is Domine, Dominus Noster by madrigalist, Thomas Morley which survives in a single set of part-books (the “Sadler Part-books”, now in the Bodleian). It helpfully notes:

Thomas Morley — ætatis suæ 19. anno domini 1576 (at the of 19, in the year of Our Lord 1576)

At age nineteen, Thomas Morley was probably in the midst of an educational institution – either at Norwich School, St. Paul’s Cathedral School, or the University of Oxford – the former two probably held LPP services and the latter certainly did. As such it is very likely this piece was also written for the LPP.

Morley’s output of educational music does not stop there. In 1597 Morley published the first edition of his charming and delightfully pretentious A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicalle Musicke; laid out in the form of dialogue, Morley amusingly casts himself in the image of Plato or Erasmus. In this work, which is a musical didactic text, Morley provides harmonisations of the psalm tones and includes several full works at the end, including:

Eheu sustulerunt

O amica mea

Domine fac mecum

Agnus Dei

These are all in Latin. Although this might be acknowledging the early-English or Continental composers of Latin works that are imitated, it is possible to achieve this imitation on a musical level with the words still in English – we have already seen the flexible contemporary attitude to the words of vocal music. So, it seems likely these works may have been associated with LPP services; this treatise was probably kept in the libraries of schools and colleges using the LPP.

The Performance of This Liturgy

The structure of this evensong is a little different to the standard collegiate or cathedral style. The main difference is the anthems. They are not part of the service. In the 1560 LPP, both mattins and evensong end after the third collect. In the 1662 BCP there is the anthem followed by additional prayers, and the grace. Most clerics these days will add prayers from outside the Prayer Book and put a blessing on the end. But, before 1662, the anthem was not actually part of the liturgy-proper. John Harper notes that Elizabethan injunctions allowed for an anthem before and after mattins and evensong.[16] He also notes that at Lincoln Cathedral the Visitors required that the anthem be followed by the collect for the preservation of the King’s majesty. Scholars generally agree that the anthem, starts out as a reformed version of the anthem of Our Lady, or Jesus that usually followed compline in the various Medieval English uses, known as the “Salve Service”.[17] The Edwardine Royal Injunction delivered to the chapter of Lincoln declares:

There shall from hensforthe synge or say no Anthemes off our Lady or other saints but onely of our lorde.[18]

This quite explicitly links the old Marian anthems to new reformed-style anthems. Over time it somehow became custom to have one before as well as after evensong, and mattins, having more-or-less, the same shape as evensong ended up book ended with anthems by analogy.

In our reconstruction we have done exactly that: at the start the choir will sing Morley’s Domine, Dominus Noster, and at the end, Weelkes’ Laboravi, which will be followed by a collect for the preservation of the King’s Majesty.

Nowadays, we are used to the organ covering the ministers’ and choirs’ grand entrance and exit as well as accompanying the congregation and choir within the service. Le Huray describes organ voluntaries at St. Paul’s Cathedral before the reading of the first and second lessons and that Edward Gibbons at Exeter had a voluntary before the anthem.[19] In our reconstruction, the organ is providing preludes to both anthems and to both lessons.

The two lessons are sung by members of the choir, and the ministers chant all their parts. Edmund Fellowes summarises the arguments of John Jebb who writes that when the Prayer Book states “say” it means “not polyphony”, and so it is acceptable to chant all the prose sections, as in the Medieval English uses. Since the spoken voice does not carry in a large building and the intoned one does (as much is admitted in the rubrics regarding lessons in the 1549 and 1552 Prayer Books) the lessons and prayers and collects are sung without the aid of microphones.[20]

The final music items are the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis which the choir will sing to Tallis’ Latin Evening Service. It is agreed among some scholars but not all that this setting was intended for the LPP.[21] Stephen Rice discusses both sides of the argument in his article. He notes the following problems:

- We cannot date the work;

- There are no tell-tale signs of it belonging to a particular Tudor liturgy;

- The LPP was never used terribly much, particularly due to Cambridge’s objections which rules out performances there;

- Tallis had no university connections.

However, there are no other surviving or mentioned paired canticle Magnificats or Nuncs for any English Latin rite – so there is no precedent for this arrangement. I think that although it is not certain, there is a good chance this setting was intended for a Latin Prayer Book service of some description; the Sarum Use never had paired canticles and indeed never had a polyphonic Nunc (there are no extant or mentioned examples). That Tallis had nothing to do with Oxford is not important, because, as we know, Reformed Latin services were not limited to universities.

Further Ritual of the LPP

As already discussed, the proponents of the LPP were likely some of the most conservative of academic clergy in the new Reformed church. Its main period of use, 1560-1649, saw a range of churchmanship from Elizabeth I’s initial conservativism and ending with Laudianism from the 1630s. Even though there may have been a generally lower churchmanship between those points, there were those who bridged the gap such as Lancelot Andrewes. The deliberate vagueness in the Prayer Book’s ritual instructions as well as the lack of official instruction meant there was a huge variety of practice. Copes could be worn for celebration of the Communion.[22] Further, we know copes were also worn by choir members. In the famous landscape of the funeral procession of Elizabeth I, the Gentleman of the Chapel Royal are pictured in an array of colourful copes.[23] This is seen again at the coronation of James II.[24]

Historically, the cope was “the correct vesture of the rulers of the choir or cantors… who… precent the psalms, canticles, and hymns”.[25] Certainly this is true of the Sarum Use.[26] Discussion by contemporary sources and scholars regarding the use of copes seems to refer only to their general, non-service-specific use, or during the Communion. As such, it is not crystal clear whether they were used at the office. Given the other ritual points regarding music, the chanting of lessons and collects, it seems the particular clerics performing this liturgy from such a conservative prayer book were keen to keep as much continuity with the Medieval English Uses as was reasonably possible. This and the fact we know the Chapel Royal coped their gentlemen in a non-Eucharistic context, it seems possible copes were used for the office (at least in this particular context).

It appears that in High Church circles incense was frequently used. Again, the theme of continuity with the Medieval English uses reappears – and it is likely incense burned in a thurible was used in all the “normal” places, including censing the altar at various points in the office (such as during the Magnificat) and Communion as well as censing the gospeller and gospel at Communion as explained by Andrewes in his various customaries.[27]

Reconstructing The Liturgy at Keble

Needless to say, Keble is not the sort of space for which the LPP was designed, nor was it a space designed to enact the words of the LPP. Its layout is unlike other Oxbridge chapels – it has a nave architecturally distinct from the quire and sanctuary, the seats in the nave are latitudinal, not longitudinal. As such, we are only using the quire and sanctuary for the enactment of The Liturgy, the nave is equivalent to an ante-chapel full of spectators. The quire will be occupied by both the choir (that is the musical one) and clergy. This mimics the enclosed quire that would normally be a college chapel.

References

[1] Streatfield, Frank, “Latin Versions of the Book of Common Prayer”, Alcuin Club Pamphlet XIX, 1964, pp. 2

[2] Act of Uniformity, 1662, accessed 9th September 2024, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp364-370#h3-s14

[3] Wray, A. (1996). The sound of Latin in England before and after the Reformation. In J. Morehen (Ed.), English Choral Practice, 1400–1650 (Cambridge Studies in Performance Practice, pp. 74-89). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511552410.005

[4] Norman L. Jones, Elizabeth, Edification, and the Latin Prayer Book of 1560, p. 179

[5] Laud, William, “The private devotions of Dr. William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury and martyr”, J.H. Parker, 1838, accessed 27th April 2023, https://archive.org/details/a589784600lauduoft/page/n173/mode/2up

[6] Bryan D. Spinks, the Rise and Fall of the Incomparable Liturgy, Chapters 1, p. 10

[7] Ibid.

[8] John Harper, the Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century, Chapter 11: the Reformed Liturgy of the Church of England (1549 – 1662), p. 175

[9] University Church Ordo for Latin Communion (20 April 2023, 8.00am), “About this Service: Latin versions of the Book of Common Prayer)”, pg. 18-19

[10] Ibid.

[11] Peter Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549-1660, Chapters 6, p. 157

[12] Ibid. p. 158

[13] Tallis, Thomas & Byrd, William, Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur, 1575

[14] MS 29376 “Tristitiae Remedium of Thomas Myriell”, British Library

[15] Weelkes, Thomas, O Vos Omnes (SSAATB): Description, Cathedral Press,

[16] John Harper, the Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century, Chapter 11, p. 179

[17] Peter Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549-1660, Chapter 7, p. 180; Bryan D. Spinks, the Rise and Fall of the Incomparable Liturgy, Chapters 1, p. 19; Harper, p. 186-7

[18] Edmund H. Fellowes, Revised J.A. Westrup, English Cathedral Music, chapter 4, p 35

[19] Le Huray, Chapter 6, p. 164-5

[20] Edmund H. Fellowes, Revised J.A. Westrup, English Cathedral Music, Chapter 3, pp.15-20

[21] David Wulstan, Tudor Music, Chapter 11, pp. 306-7; Stephen Rice, Reconstructing Tallis’s Latin Magnificat and Nunc dimittis

[22] Gee, H, “The Elizabethan prayer-book & ornaments”, Macmillan, 1902, pp. 150-60; Phillips, Benjamin, “Worship the Lord in the Beauty of Holiness – the Celebration of the Eucharist according to the Laudian Movement” http://benjaminphillipsblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/worship-lord-in-beauty-of-holiness-4.html, accessed 26th April 2023

[23] Drawings of the funeral procession of Elizabeth I, accessed 26th April 2023, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/drawings-of-the-funeral-procession-of-elizabeth-i

[24] Sandford, Francis, The History of the Coronation of the most high, most mighty, and most excellent monarch, James II … and of his Royal Consort Queen Mary, solemnized in the Collegiate Church of St Peter … on 23rd April, … 1685, 1687

[25] Leonard Spiller, Some Notes on Copes. Project Canterbury, London: The Warham Guild, 1939.

[26] Harper, John, tr. Howard Henry, “3.1: The New Customary, From Oxford, Corpus Christi College, MS 44, In the Order of the MS [NCC]”, accessed 26th April 2023, http://www.sarumcustomary.org.uk/exploring/PDF_files/3.1%20NCC/NCC-E.pdf

[27] Addleshaw, G. W. O., “The High Church Tradition”, Faber and Faber 1947

Bibliography

Streatfield, Frank, “Latin Versions of the Book of Common Prayer”, Alcuin Club Pamphlet XIX, 1964

“Morley’s Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke.” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, vol. 43, no. 713, 1902, pp. 457–60. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3369667. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

Phillips, Peter. “‘Laboravi in Gemitu Meo’: Morley or Rogier?” Music & Letters, vol. 63, no. 1/2, 1982, pp. 85–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/736043. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

Jebb, John “The Choral Responses and Litanies of the United Church of England and Ireland: Collected from Authentic Sources”, George Bell 1847

Jebb, John “The Choral Service of the United Church of England and Ireland: Being an Enquiry Into the Liturgical System of the Cathedral and Collegiate Foundations of the Anglican Communion”, J.W. Parker, 1843

Rice, Stephen. “Reconstructing Tallis’s Latin ‘Magnificat’ and Nunc ‘Dimittis.’” Early Music, vol. 33, no. 4, 2005, pp. 647–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3519586. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

Jones, Norman L. “Elizabeth, Edification, and the Latin Prayer Book of 1560.” Church History, vol. 53, no. 2, 1984, pp. 174–86. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3165354. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

David Wulstan, Tudor Music, Chapters 10-11, Littlehampton Book Services Ltd, 1985

Edmund H. Fellowes, Revised J.A. Westrup, English Cathedral Music, Chapters 3-5, Methuen young books; 5th edition, 1969

Bryan D. Spinks, the Rise and Fall of the Incomparable Liturgy: The Book of Common Prayer, 1559-1906 (Alcuin Club Collections, 92), Chapters 1-2, SPCK Publishing, 2017

Peter Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549-1660, Chapters 6-7, Oxford University Press, 1967

University Church Ordo for Latin Communion (20 April 2023, 8.00am), “About this Service: Latin versions of the Book of Common Prayer)”, pg. 18-19

Gee, H, “The Elizabethan prayer-book & ornaments”, Macmillan, 1902

Addleshaw, G. W. O., “The High Church Tradition”, Faber and Faber 1947

Morehen, J. (Ed.). (1996). English Choral Practice, 1400–1650 (Cambridge Studies in Performance Practice). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511552410

Laud, William, “The private devotions of Dr. William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury and martyr”, J.H. Parker, 1838, accessed 27th April 2023, https://archive.org/details/a589784600lauduoft/page/n173/mode/2up