Thoughts on our recent Advent-themed concert at St Olave, Hart Street, and upcoming Sarum reconstruction at Great St Bartholomew, Smithfield.

On the 4th December, we performed in London for the second time, at St Olave, Hart Street. Yesterday, we announced the first in a number of reconstructions we have planned at Great St Bartholomew in Smithfield, London. These are the first in what is hopefully a growing number of concerts and liturgical events in the capital. The full programme from our concert was as follows:

- O Sapentia, Anon. (Sarum Plainsong)

- Veni, Veni Emmanuel, Anon. (13th Century)

- Gloria “Spiritus et Alme”, Queldryk (fl. 14th Century)

- Prevent us, O Lord, William Byrd (c.1539–1623)

- There is No Rose – Anon. (15th Century)

- Stella Celi – John Cooke (fl. 14th Century)

- Mater Christi – John Taverner (d. 1545)

- Now doth the Citie – John Amner (1579–1641)

- O Nata Lux – Thomas Tallis (d.1585)

- O Sacred and Holy Banquet – Thomas Tallis (d.1585)

- Agnus Dei, Oliver (fl. 14th Century)

- Ave Verum – William Byrd (c.1539–1623)

- Alle Psalite Cum Luya – Anon. (c. late 13th Century)

- O Virgo Virginum – Anon. (Sarum Plainsong)

The programme follows an Advent theme. We started and ended with the first and last “O antiphons” in the Sarum order: O Sapientia, and O Virgo Virginum. The O antiphons are a sequence of Magnificat anthems used in the latter half of Advent. The texts, though short, draw on largely Old Testament images and themes, eventually finishing with the Virgin Mary. Together, they spell out the acrostic “vero cras”, meaning “truly, tomorrow” alluding to the immenent coming of Christ. O Virgo Virginum is appointed for use on the 23rd December; the following day sees the first services of Christmas proper, the morning Offices and Mass of the Eve of the Nativity, follwed by first Evensong/Vespers of the Nativity itself.

Our next item, the two-part anonymous c. 13th century “Veni, veni, Emmanuel,” is one of the earliest known examples of the carol. Set for two equal voices and sung in free time, the upper voice is a simple, yet beautiful, countermelody weaving around the original melody. The text is mostly a poetic rendering of the “O antiphons”.

Much of the rest of the programme followed this play between the Virgin Mary (as in “O Virgo Virginum”) and the incarnation (“vero, cras”).

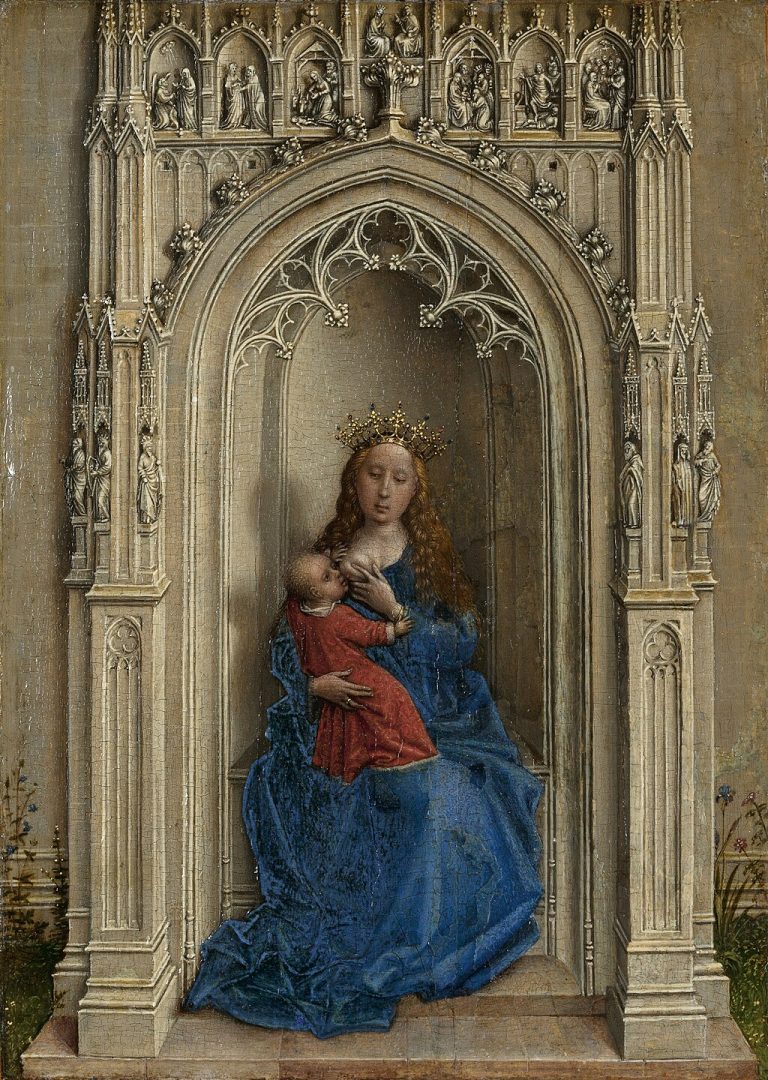

The upper voices sung “Ther is no rose of swych vertu”, a three-part Medieval Carol in honour of the Virgin Mary as the mother of Christ, from the 15th century. The lower voices responded with Cooke’s “Stella Cæli”. This text, though commonly associated with plagues, puts as its subject the Virgin Mary suckling the Christ-Child, much like its better-known companion the “Nesciens Mater”. Unlike the “Nesciens”, it uses the image from the hymn “Ave Maris Stella”, of Mary as Queen of Heaven, shining chief among stars and guiding men across land and sea. Pertinently, it is reminiscent of the star that guides the Magi to the new-born Christ. Our final Marian piece is Taverner’s sumptuous “Mater Christi”. The music is split between trios and duets across different parts, as well as big chordal full-chorus moments. The text asks for Mary’s intercession, and praises both Christ and Mary with various food and drink metaphors, such that we may share in the heavenly banquet.

This neatly leads us to the final section of our programme, focussing on the Incarnation. We opened this section with Tallis’ famous “O Nata Lux”, again the text plays with the idea of light as a guiding presence, but also the idea of God cloaking Himself in human flesh for our salvation. This was followed with more Tallis, “O Sacred and Holy Banquet” a contrafactum of the Eucharistic motet “O Sacrum Convivium”. Then came Byrd’s “Ave Verum”. This delicate, slow-paced, largely chordal piece full of piercing false relations, exactly matches the visceral, painful nature of the text which pictures Christ, the son of Mary, crucified, pouring forth blood and water. This highlights some of the similarities between the two penitential seasons, Advent and Lent.

Our final piece in this section was the anonymous “Agnus Dei à 4” from the Old Hall Manuscript. This is the piece sung at one of the focal moments of the Mass, after the consecration.

Between these two sections, we sung an old favourite, Amner’s “Now doth the citie”, which starts like one of the great Tenebrae lamentations, such as those by Tallis or White, but then adopts a more hopeful tone. This fits well with the Advent theme, the penitential and the unfulfilled sense of longing, followed by something more optimistic.

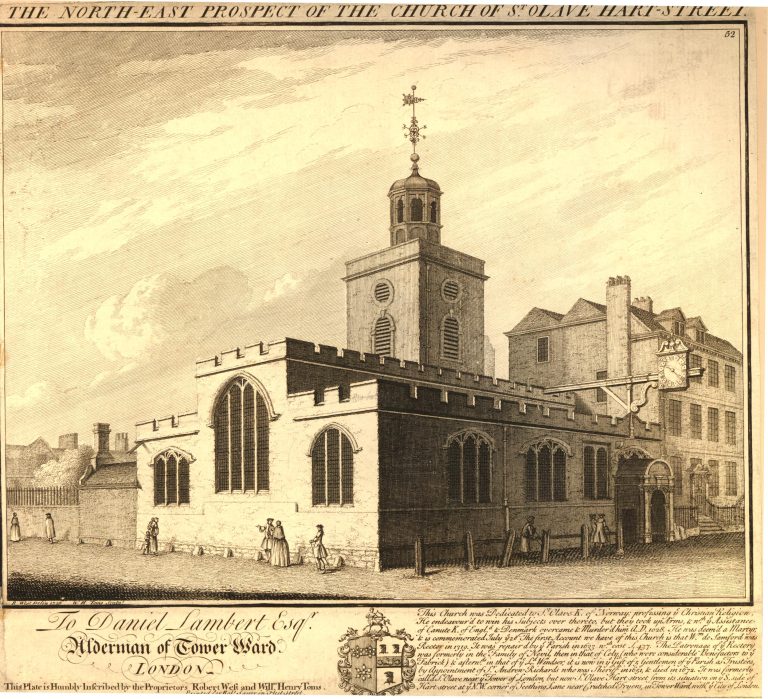

St Olave’s, Hart Street, is one of the few extant Medieval city churches, having survived the Great Fire of London and the Blitz (just). It was wonderful to perform in a church that, once upon a time, may well have heard that music before. I was informed by a gentleman in the audience that the Jacobean monument to the left of the Communion Table was in honour of friends of the Byrd family, who had been beneficiaries in their will. I had no idea, and so it was a wonderful coincidence that we had two pieces of Byrd down that day.

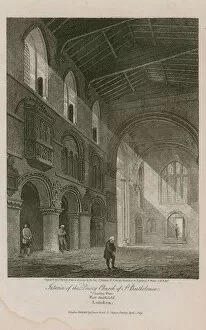

Advent and Lent, the two penitential seasons, are mirrored by two celebratory periods of Christmastide and Eastertide. The Christmas period is therefore, not simply twelve days, but forty, lasting till Candlemas eve. Having marked the start of the build-up to Christmas, we will also mark the end of Christmastide. Our next event takes place on Candlemas eve – the 1st of February. This will be a reconstruction of England’s foremost Medieval liturgy, the Use of Sarum in St Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield. We previously have done Vespers, Compline and Salve according to the Use of Sarum (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uag_2RMD194), but this time it will be a Mass, but not just one Mass, four. There will be the main High Mass at the high altar, but around the ambulatory of the church there will be three other spoken masses going on simultaneously, including of Our Lady, in the Lady Chapel, the site of a 12th century Marian apparition.

The Use of Sarum is a secular use (i.e. for non-monastic churches), but Great St Bartholomew was not a secular church. It was an Augustinian priory. The Austin friars, however, in England followed the Use of Sarum so this is the liturgy that would have been used in that church in the Medieval period.

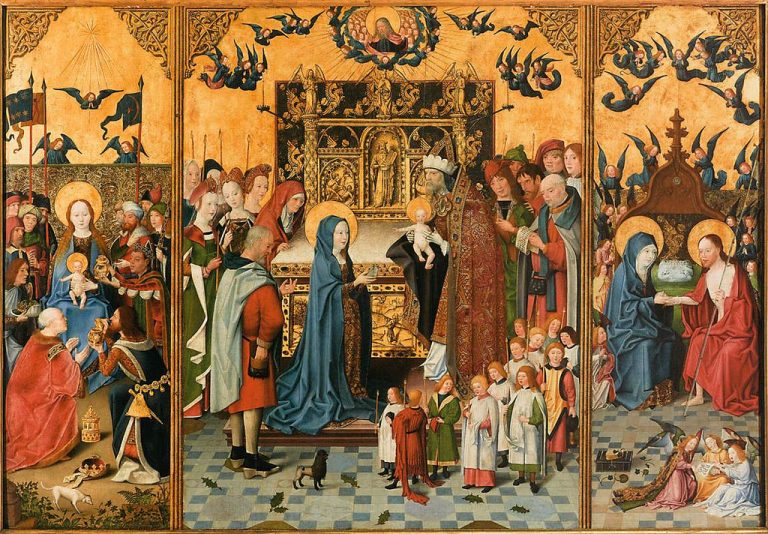

Much of the Advent texts above mention either Christ or Mary as a light of some description. Through the course of the Christmas period light, thanks to the famous star, becomes symbolically important. Epiphany, 6th January, celebrates the arrival of the Magi, led by the star. In Medieval England, it was typical for Epiphany vestments to be decorated with stars. At Candlemas too, so named because the liturgy involved the carrying and blessing of many candles, light was important. The great Medieval Homilist, John Mirk this custom explains in his Festial:

Wherfor, ȝet yn mynde of þys processe, when a woman cometh to þe chyrche-dyrre tyll þe pryst come and cast holy watyr on hyr, and clansuf || hur, and so takyth hyr by þe hond, and bryngyth hur to þe chyrche, ȝeuyng hur leue to come to þe chyrch, and to goo to hur husbandys bed. For and scho haue ben at hys bed befor, scho most take hor penance and he, bothe. Þerfor holy chyrch maketh mynde þys day of candels offryng. ȝe seen, good men, þat hyt ys comyn ȝe to all crysten men forto come to þe chyrche þys day, and bere a candyll yn processyon, as þagh þay ȝedya bodyly wyth oure lady to chyrch, and aftyr offyr wyth hyr yn worschip and high reuerens of hur.

Then now hereth how þys worschip was furst yfond, when þe Romaynes by gret chyualry conquered all þe world. For þay wern euerous yn hor doyng þat retten not to God of Heuen þat ȝaf horn þat euere ; but made horn dyuerse goddys, aftyr hor owne lust. And soo, among othyr, þay hadden a god þat was callet Mars, þat was byfor þat tyme a chyualrous knyght, and an euerous yn batayle. “Wherfor þay called hym god of batayle, prayng ȝorne to hym for helpe. And for þay wolden spede fe bettyr, þay dyd gret worschyp to his modyr þat was callet Februa ; aftyr þe whech woman, as mony haue opynyon, þys mon þat now ys was called February. Wherfor þe fyrst day of þys mone þat now ys Candylmasse-day, þe Romans wold goo al nyght about þe cyte of Rome wyth torches, and blasus and canduls brennyng, yn worschip of þys woman Februa, hopyng for þys worschip to haue þe rayþyr helpe of hyr sonne Mars yn hor doyng.

Then was þer a pope þat heght Sergyus. For he segh cristen men drawe to thys mawmetry, he þoght to turne þat foule custom ynto Goddys worschyp and oure lady Seynt Mary, and commaundyd all cristen men and wymmen forto come þys same day to a chyrche and iche on offyr a candyll brennyng || yn worschyp of our lady and hur swete sonne. Soo yche maw aftyr, by processe of tyme, lafton þat worschip þat þay dyden to þat woman Februa, and duden worschip to our lady and to hyr sonne, so þat now þys solempnyte ys hallowed þrogh crystendame, and yche man, and woman, and chyld of age comefe þys day to þe chyrche, and offren brennyng condyls ; as þogh þay wer bodyly wyth our lady to chyrche, on chyld hopyng for þys reuerens þat þaydon to hyr yn erþe, to haue a gret reward þerfor yn Heuen. And so þay may be sure þerof. For a candyll brennyng bytokenyth cure lady, and hor sonne, and a man hymselfe; for a candyll ys made of whyte weke and of wax brennyrg wyth fyre. Þus Crystys whyt soule was hydde wyth his monhede and brenneþe wyth þe fyre of his Godhed ; hit bytokenyth also our ladyys modyrhode and maydynhede, lightnet wyth þe fyre of loue ; hyt bytokeneth also yche good man and woman þat doþe good dedes wyth good entent, and yn full loue and charite to God and to his euen-cristen. Wherfor yf any of you haþe soo trespassyd to his neghtbur wherby þat þys candyll of charyte ys qwenchet, furst go he and acord hym wyth his neghtbur, and so tend his condyll aȝeyne, and þen offyr his condyll to þe pryst. For þys ys Godys commaundment ; and elles he lesyth hys meryt of his offryng.

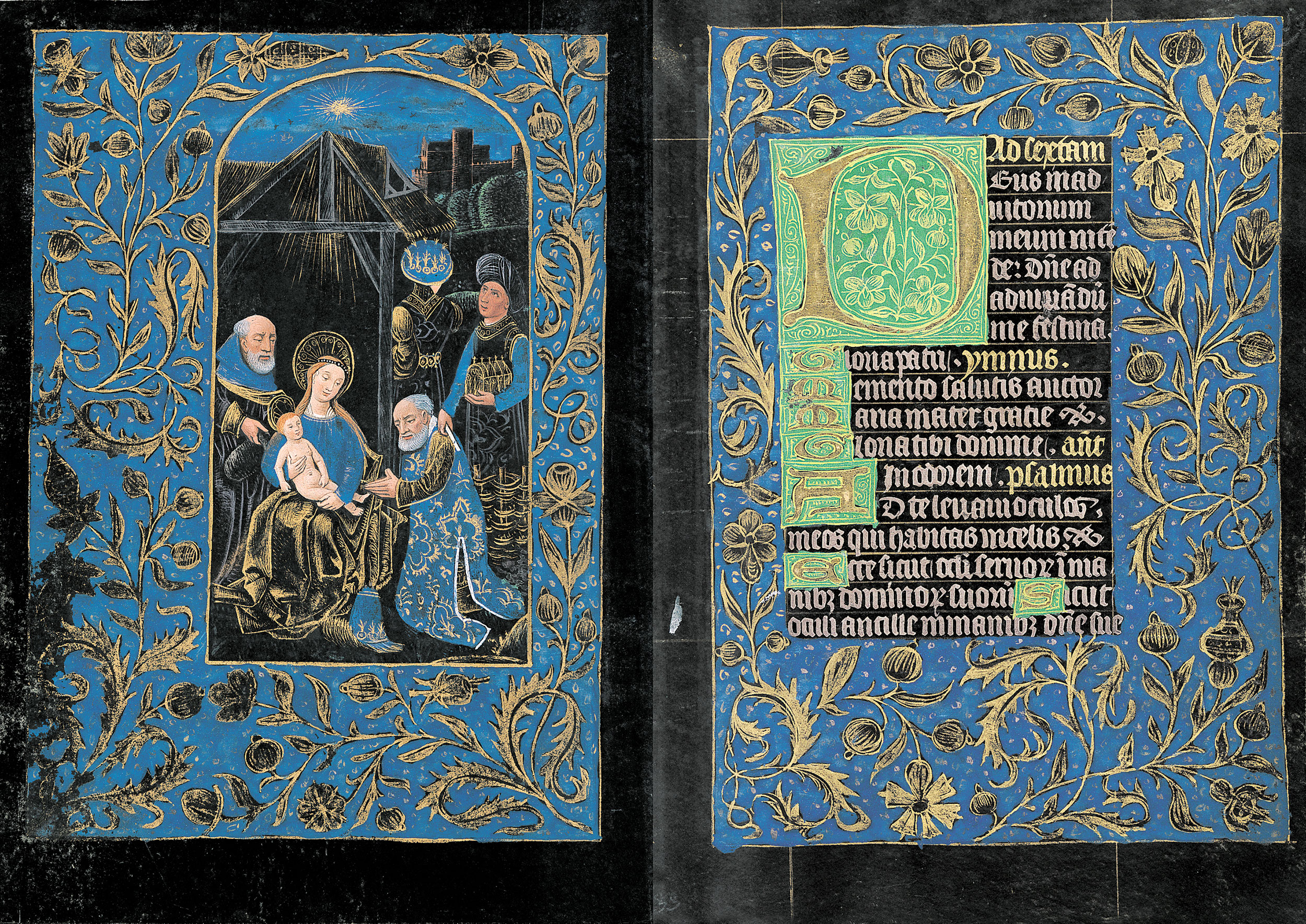

Candlemas processions and services, with laity clutching their lights is common in late Medieval and Renaissance artwork. This great celebration and day of obligation represents the end of the Christmas festivities. Mirk emphasises the part Mary plays; the Church maintains Candlemas as a feast of Our Lady and not Our Lord. This has implications in the Sarum use, the Gloria, for example, adds various tropes known as “Spiritus et Alme”. This practice largely disappeared after the Counter-Reformation. It exciting that we have picked a feast that contains this archaic quirk. We will sing a setting by the composer known as Queldryck. In the same vein, the service will end with the Marian antiphon, which will be Cooke’s “Stella Cæli”, again picking up on the light imagery. Though the proper place for this Marian devotion, known as the “Salve Service” after the most popular Marian antiphon, was after Compline, it was commonly done after Mass as well, as still is standard in the Mozarabic Rite.

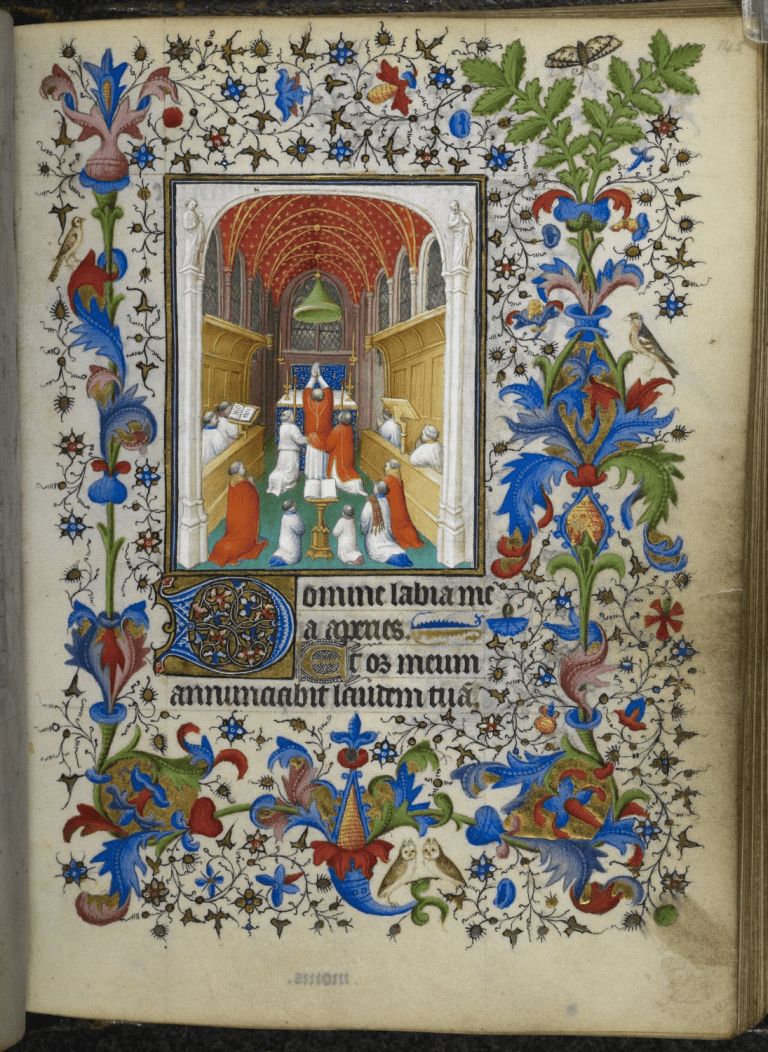

All the polyphony will be taken from the Old Hall Manuscript. Dating from the late 14th Century, this is one of the most significant collections of English Medieval liturgical polyphony. The Marian tropes suggest much of it was clearly designed for services of Our Lady. This is typical, as many choirs were set up simply for the purpose of singing the services of Our Lady. The music at this service will be sung only by the lower voices of the ensemble.

We are very grateful to the various churches that host us for our concerts and service. We are greatly looking forward to working with Great St Bartholomew’s on this series of historical services.

Please do follow for more updates and blog posts if you have enjoyed this one!